Countless changes happen to a woman during pregnancy. Among the most obvious are the physical and hormonal changes including weight gain, increased estrogen and progesterone, and shifts in metabolism. As a first-time mother-to-be, I am overwhelmed with all of the changes, both seen and unseen, my body is experiencing. Of course, the physical and hormonal changes are just a part of the complicated journey. What about all of the unseen, and often not talked about, changes that we experience? As a clinical microbiologist, I want to know as much as I can about how my pregnancy is impacting the smallest, most numerous, and often underappreciated cells in my body – microorganisms! While nearly every part of the body is affected by pregnancy, I aim to understand how vaginal flora changes and the impact of those changes on mom, baby, and what it may mean for post-partum recovery and future deliveries.

What is Normal Vaginal Flora?

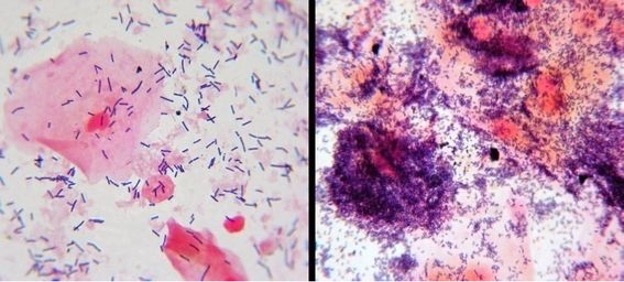

Healthy women play host to several bacterial species; one of the most prominent and important include Lactobacillus spp. (1). These microorganisms contribute to creating the lower pH (<4.5) of the vagina by producing lactic acid. The low pH aids in protection from infection by other microorganisms and viruses (9, 10). Even a slight increase in pH to 5.0 has been correlated to bacterial vaginosis (13)! Bacterial vaginosis can look (and feel) different for different women. Usually, it is caused by an imbalance in the vaginal flora which allows for the overgrowth or increase in “bad” bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus and other anaerobic bacteria. Also, the common yeast infection from Candida albicans can spell trouble for us expecting moms (11).

What Changes During Pregnancy?

While some things change dramatically during pregnancy, others aim to remain the same – to help stabilize the mom-to-be, the overall richness and diversity of bacteria in the vagina generally decreases during pregnancy (14). This means the number of Lactobacillus increase; thus, maintaining the low pH of the vagina and reducing the risk of infection from other bacteria. Sounds great! Of course, some of us are not so lucky and things may get out of balance.

What Are The Implications of a Less Stable Vaginal Microbiome, Bacterial Infections, or Yeast Infections and How May it Affect my baby?

Higher bacterial diversity, meaning less Lactobacillus spp., more Gardnerella vaginalis and even Ureaplasma, have shown strong associations with an elevated risk of preterm birth (2, 5, 8). More specifically, as the pH increases and the vaginal microbiome changes the risk of infection increases and leads to a potentially harmful immune response. The immune response causes inflammatory reactions which can cause preterm uterine contractions and weakening of fetal membranes (6, 12). Additionally, colonization with Candida albicans has been correlated with higher rates of preterm birth (4). As if the uncomfortable symptoms of bacterial vaginosis and yeast infections are not enough!

Let’s say you have a healthy pregnancy with normal vaginal flora – Is That Where The Risk For Trouble Ends?

Unfortunately, no. While your balance of Lactobacillus spp. may have been healthy and ideal during pregnancy those days are numbered. After birth, the vaginal microbiome goes through significant changes. Those helpful Lactobacillus start to dwindle, and the bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis become enriched – even if you were not prone to infections before pregnancy (8). For some mothers the vaginal microbiome even resembles the gut microbiome (2). Some of these imbalances have been documented to last as long as a year after delivery which may also explain the increased risk of preterm birth in closely spaced pregnancies due to less time for the mother’s vaginal flora to return to normal and stabilize (2, 3).

Together, these factors may directly affect the early colonization of baby during vaginal birth. Mode of delivery and its effects on colonization of the newborn is another area of extensive research that I aim to understand in a later post, stay tuned!

As expectant moms we can only do our best to prepare our bodies for birth. Some things are beyond our control and while it is important to note the risks of vaginal infections during pregnancy it does not mean every infection will lead to preterm birth or complications. As for solutions to some of these potential issues always ask your doctor and listen to their advice regarding your health and your baby’s. What is right for you and your baby may not be right for someone else.

Good luck moms!

M. DeGarmo MS, M(ASCP), Clinical Microbiologist

References

- Aagaard, K., Riehle, K., Ma, J., Segata, N., Mistretta, T. A., Coarfa, C., et al. (2012). A metagenomic approach to characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy. PLoSONE 7:e

- DiGiulio, D. B., Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Costello, E. K., Lyell, D. J., Robaczewska, A., et al. (2015a). Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, 11060–11065.

- DiGiulio, D., Callahan, B., McMurdie, P., et al.Microbiota during pregnancy. Sep 2015, 112 (35) 11060-11065

- Farr, A., Kiss, H., Holzer, I., Husslein, P., Hagmann, M., and Petricevic, L. (2015). Effect of asymptomatic vaginal colonization with Candida albicans on pregnancy outcome. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 94, 989–996.

- Hyman, R. W., Fukushima, M., Jiang, H., Fung, E., Rand, L., Johnson, B., et al. (2014). Diversity of the vaginal microbiome correlates with preterm birth. Reprod. Sci.21, 32–40.

- Lajos, G. J., Passini Junior, R., Nomura, M. L., Amaral, E., Pereira, B. G., Milanez, H., et al. (2008). [Cervical bacterial colonization in women with preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes]. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet.30, 393–399.

- Machado A, Cerca Influence of Biofilm Formation by Gardnerella vaginalis and Other Anaerobes on Bacterial Vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2015 Dec 15;212(12):1856-61.

- MacIntyre, D., Chandiramani, M., Lee, Y. et al.The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the postpartum period in a European population. Sci Rep 5, 8988 (2015).

- Martin, H. L., Richardson, B. A., Nyange, P. M., Lavreys, L., Hillier, S. L., Chohan, B., et al. (1999). Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. Infect. Dis.180, 1863–1868.

- McLean, N. W., and Rosenstein, I. J. (2000). Characterisationand selection of a Lactobacillus species to re-colonise the vagina of women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Med. Microbiol. 49, 543–552.

- Nuriel-Ohayon, M., Neuman, H., Koren, O., Microbial Changes during Pregnancy, Birth, and Infancy. Front Micro. 2016Jul 14; 1031 (7).

- Park, J. S., Park, C. W., Lockwood, C. J., and Norwitz, E. R. (2005). Role of cytokines in preterm labor and birth.

- Ravel, J., Gajer, P., Abdo, Z., Schneider, G. M., Koenig, S. S., McCulle, S. L., et al. (2011). Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.108(Suppl. 1), 4680–4687.

- Romero, R., Hassan, S. S., Gajer, P., Tarca, A. L., Fadrosh, D. W., Nikita, L., et al. (2014a). The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota of normal pregnant women is different from that of non-pregnant women. Microbiome 2:4.

- Image by https://std-symptoms.com/bacterial-vaginosis